In these modern times, traditional textiles or fabrics have found their way into the spotlight, in exhibits or come Heritage Month and Buwan ng Wika. More recently, these fabrics have also found new life as they are stitched into today’s fashion, borne away from their glass showcases in museums. But at the peak of their revival, these fabrics have also sparked debates on cultural appropriation, an issue that has caused concern in different sectors of society. As a result, we struggle to recognize and juggle the fine line between appreciating heritage and misappropriating centuries-old cultures.

While there is nothing wrong with being proud of our country’s rich culture, there is also the danger of mistranslating it and therefore showing it disrespect. This then results in cultural appropriation, which Marlon Martin, chief of Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement and founder of the Ifugao Heritage School, defines thus: (1) when you claim a culture to be yours when it isn’t; (2) when you have no knowledge of the context of that cultural property; and (3) when there is an act of disrespect.

Cultural appropriation is not a new topic. In fact, various brands and celebrities have been accused of this in the past. Do you remember when Chanel sold a boomerang that cost $1,500? The boomerang belongs to the poorest demographic in Australia, the Aborigines. By emblazoning its brand’s logo on it and turning it into a status symbol, the fashion house was accused of creating a mockery of the culture. Likewise, the Kardashians have received a lot of flak for sporting cornrows and wearing a niqab and Native American headdresses—aspects of certain cultures that they used as styling tools without giving significance to their value in their respective cultures.

With the big fuss that people are creating over these incidents, we now ask: What’s the deal? Why is no one getting punished over this? It’s simply because cultural appropriation is not a crime. But should it be?

Culture is fluid, always shifting, and is meant to be shared; but when borrowing one’s culture or using it as inspiration becomes exploitative—meaning, you take credit and make more profit than the owners—you can be guilty of cultural looting.

Marlon reiterates that they’re “not asking for individual recognition, [but mere attribution to the group of people] who owns the patterns [on the fabrics].” Without credit, such patterns would be recognized and referred to as this certain brand’s work. But that’s just the tip of the issue. In a society where money is one of its primary pillars, local weavers receive the least financial compensation. Their products, made laboriously with love, are bought at cheap, bargain prices and resold at a steeper and heftier price tag.

Cultural appropriation does not simply devalue certain aspects of our and others’ heritage or make you seem ignorant. Cultural appropriation on the commercial level can siphon profits from struggling indigenous communities that could have benefited from this to revive and sustain their own culture—or for some, to simply survive.

The government has yet to explore interventions that can protect these traditions and cultural symbols. In the absence of these interventions, Marlon proposes an easier, albeit very old, solution: ethics. It all boils down to one’s sound judgment—on the end of both the buyer and the seller.

Marlon describes the sad reality of the Ifugao weavers, “Most of our weavers weave so they can have something to eat for the week.” Faced with this predicament, one cannot blame them, therefore, for selling even what is sacred to them for basic survival. “[The death blanket for example.] ‘Yung magbebenta, ‘di ka sasagutin na ‘di pwede gamitin ‘yan. They need to sell. Kung minsan tawag ng pangangailangan. (The sellers won’t say you can’t use a certain fabric. They need to sell. Sometimes, out of dire need.)”

Learning this heartbreaking situation, we now ask: How can we help them make a living, promote a piece of Filipino culture, and appease our personal interests without disrespecting anyone? Is there still a rightful place for traditional textiles in a highly westernized society such as ours?

Marlon breaks down the solutions to this into five concrete ways:

Educate yourself.

Read books; do your research before buying anything. “We have Facebook in Ifugao. You can ask us.” Know what certain colors, symbols, or actions mean for the locals. More than this, understand your boundaries when it comes to what you can use commercially and what should be left alone and kept solely for the use of the people who own the said cultural symbol.

Do not buy purely for aesthetic purposes.

Marlon warns, “Textiles have always been objects of commerce. We’ve been selling death blankets kasi may mga weavers talaga na specialty nila is making death blankets and they sell it to people who need it, to people who are going to use it as death blankets. So common ‘yung bentahan na ‘yan. Here comes somebody from outside who buys the death blanket and then ginawang gown or ginawang bed cover. So doon maalarma ‘yung may-ari ng culture.”

Ga’mong or blankets for the dead are laid over the deceased. These blankets are woven with specific patterns so the ancestors can easily locate the lost soul and reunite him with members of his family already in the after-life. Marlon shares that when his grandmother, who is also weaver, passes on, she will have over forty ga’mongs laid over her body as she is connected to most families in Kiangan, Ifugao. That said, using death blankets for contemporary fashion—even in its most common design iterations—is a complete mockery of, and a show of disrespect for, both the living who are mourning and those who have passed on.

This can be avoided by simply asking the weavers to modify the designs for you. Marlon makes it clear that the indigenous people do not own the weaves or textiles, per se. What makes a certain fabric sacred or what makes it their own, though, is how they arrange the particular patterns and its colors

Do not haggle . . .

. . . and then sell their fabrics for an exorbitant amount of profit. Remember that what you are purchasing is a piece of traditional art translated into wearable textile. They took days, if not weeks, to weave. More important, it’s a piece of our culture and our history.

Give credit where it is due.

Bontoc weaves are different from the Ifugao’s despite both coming from the northern provinces. Do not simply label them as “ethnic prints.” Their art is their way of preserving their history as part of the people who own the said culture. Let future people be able to trace back to them what is rightfully theirs.

Collaborate with the locals.

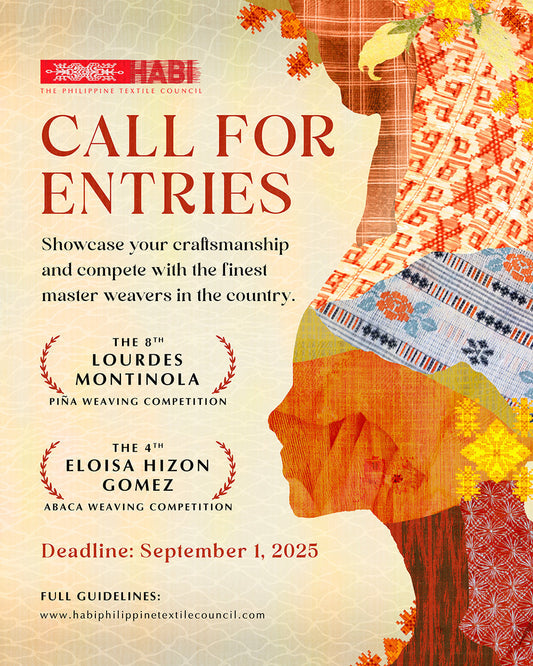

They know best about their culture. Immerse yourself in their culture and engage with the locals. Hire them as your supplier or find local organizations, like HABI: The Philippine Textile Council, to act as a bridge between you and these locals. There are groups who have dedicated themselves to reinvigorating and ethically reviving the use of Philippine indigenous textiles in modern fashion.