Since HABI: The Philippine Textile Council was organized 10 years ago, there has been a resurgence in the handloom weaving industry not just in the Cordillera but all over the country. Designers have taken the initiative of incorporating our indigenous textiles in fashion and home wares while academics have embarked on research to document traditions, techniques and designs. These developments have been very gratifying for us in HABI because from the start, our vision was of a vibrant weaving world in which traditional fabrics are preserved and used in the current lifestyle.

HABI was first set up with the realization that the weaving industry was dying. The country’s major textile mills which were set up in the 1950’s had closed down and much of the cloth available was imported. It was also noted that among the practitioners of handloom weaving, many were either ageing or dead.

The Problem

The problem, when we began HABI, was how to resuscitate the weaving industry. In our assessment of the situation, we perceived the absence of readily available raw materials to transform into cloth. Pure cotton thread, which is the essential element of most of our textiles was not being produced in the country. Only polyester yarns or cotton blended with polyester could be had for weavers to work with. This condition brought about a deterioration in the quality of textiles that our weavers were producing and reduced the market value of handwoven cloth.

The HABI Cotton Advocacy

Recognizing this, HABI embarked on its Cotton Advocacy, a drive to revive the spinning pure cotton threads and weaving with it. We partnered with the Department of Agriculture’s special agency for natural fibers (PhilFIDA) and engaged farmers in the growing of cotton by offering to purchase all their harvests. Then, with the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), we endeavored to get seed cotton spun into yarns. The next hurdle was the weavers who put up the usual resistance to change, preferring to continue to work with polyester-cotton. Fortunately, after introducing pure cotton to certain weavers, they realized the difference and the superior quality of pure cotton textiles. A convincing factor for the weavers was the higher price that pure cotton fabrics fetch in both the local and global markets.

HABI managed to produce 100% pure cotton yarns that is entirely Philippine grown. A demand for pure cotton has come about however, at the moment, we are unable to fill that demand. This is not an unhappy problem, however, and hopefully, it will be overcome soon.

In The Cordillera

Still, the problem persists. In the Cordillera, yarns for weaving have to be acquired from Divisoria in Manila or through middle men who markup their merchandize and thus raise the final cost of handwoven products.

Why not grow cotton in the Cordillera and process it right here in the region? This would create a new source of income for farmers and that income would have a quick return on investment since the crop is harvested within 6 months. Cotton can even be grown in pots and backyard plots.

Sustainability

PhilFIDA has installed, in Ilocos Norte, Antique, and Zamboanga, micro spinning facilities capable of producing yarns from cotton grown in those areas. I would propose a similar arrangement in the Cordillera, if the cultivation of cotton could be encouraged and started here either by private enterprises or the Department of Agriculture. Locally grown and spun cotton yarns have a reduced carbon footprint that would qualify it as a sustainable enterprise. Furthermore, organic cotton will increase the value of the textiles produced with it and place those textiles in a market niche that is currently in great demand by discerning millennial consumers.

Other Natural Fibers

Aside from cotton, other natural fibers such as abaca, ramie and silk can be grown and produced in the Cordillera. Silk production has been in the development stage for years in Benguet. Perhaps soon, it will finally take off as a sunrise industry with support from innovative entrepreneurs like the clothing company, Bayo which, as I speak, is working with silk cocoon farmers in Atok.

What I hope to leave with listeners today is the dream of vibrant Cordillera Textile industry. All the elements to make this dream happen are within easy reach. The raw materials can be had with some effort but, best of all, the skills and talents are there to capitalize on. Dreams really do come true, as the song goes.

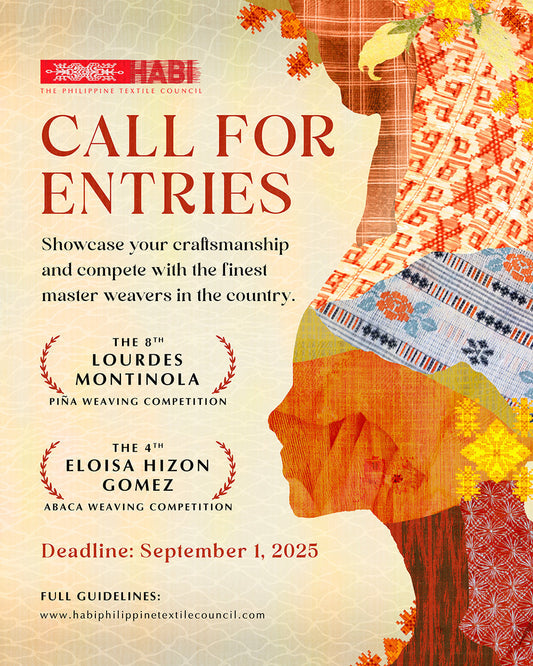

Competitions

One more thing. Stimulating creativity and innovation has been a special endeavor of HABI and one of its more satisfying initiatives. Four years ago, we held the first Lourdes Montinola Piña Weaving competition. The exercise showed us the effectiveness of contests in flushing out the best talents and raising the bar for quality. Allow me to show now a virtual tour of the entries in the weaving competition on its fourth year.

How beautiful, diba? From year one to year four, we savored textile creations that improved on the previous years’ entries. Old forgotten techniques were revived and daring innovations were introduced. This year, two new awards were given – one for innovation and another for an outstanding weaver under 30 years old. And the good news is – many young weavers participated in the competition. In fact, the younger weavers garnered the majority of the prizes. So there is now hope for the sustainability and future of the piña weaving industry. We are assured that it will be carried forward by young and imaginative talents.

A significant consequence of the Lourdes Montinola Piña Weaving competitions is the raised value of piña cloth. Weavers are now selling their pieces like works of art and earning much more. After the exhibit at Silver Lens Gallery in Manila, the entries were placed on sale in HABI’S website. Orders have come in from Europe and the United States because online merchandising opens opportunities in the borderless global market.

[The online promotion of artisan weavers and marketing of handloomed textiles on its website is a HABI initiative spurred by the pandemic but I can talk more about that at some other time.]

A similar competition for the Cordillera can be devised revolving around the utilization of locally grown cotton and natural dyes. Perhaps, the Departments of Tourism and of Trade and Industry in the Cordillera could spearhead such a competition. The private sector might be enticed to provide cash prizes with vested interests such as Narda’s Handloom Weaving and the Easter School Weaving Room as major sponsors.

The promotion of creativity and innovation is, after all, a function of governance and government agencies. While it doesn’t take much effort or resources to conduct contests that challenge competence, the results are always a form of excellence. Thus, I urge government agencies to underwrite such events in partnership with the private sector. HABI would be happy to help.